Espero que más que todos nuestros deseos, seamos felices y plenos el año que entra, y que luchemos por ello. Un fuerte abrazo.

viernes, diciembre 29, 2006

domingo, diciembre 24, 2006

miércoles, diciembre 20, 2006

Obispo quiere ser presidente

lunes, diciembre 18, 2006

Una mujer presidente de la Suprema Corte? ¿Porqué no?

Una mujer para presidente de la Corte

Prefiere 47% de mexicanos a una mujer para presidir la Corte

El próximo 2 de enero los ministros de la Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación tendrán que elegir de entre seis candidatos quién ocupara el cargo de presidente. Hay seis ministros inscritos para el cargo, entre ellos una mujer: la magistrada Olga Sánchez.

Aunque a los electores nos dejan al margen de la elección de los que encabezan el Poder Judicial, le preguntamos a la gente si preferirían que al frente de la Suprema Corte quedara una mujer o un hombre, y las opiniones se inclinaron dos a uno en favor de la opción femenina.

Cuando preguntamos en concreto, con los nombres de los ministros que aspiran al cargo, la ventaja de la ministra Sánchez es todavía mayor, llegando a 51% de las preferencias contra 27% de todos sus contrincantes juntos.

La impartición de justicia es un tema controvertido y hoy más que nunca prioritario y para los públicos, cualquier mujer y en especial la ministra Sánchez tendría cualidades específicas que no se perciben en sus colegas varones.

Ojalá y los ministros el próximo 2 de enero al menos tomen en cuenta la opinión que tenemos los electores sobre este asunto. Yo en lo particular me sumo a los que piensan que nombrar a Olga Sánchez presidenta de la Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación sería un gran acierto.

| |

La hipocresia del PRI y el PRD

Del Reforma de hoy:

María Amparo Casar

María Amparo CasarSiempre no

En materia presupuestal hay dos hechos irreductibles. Primero, son los diputados los que deciden cuánto se gasta y en qué se gasta. Segundo, los diputados llegan a su curul a través de los partidos. No es de extrañar entonces que los diputados propongan un "autoaumento" de mil 300 millones para sí mismos (adicionales al 13 por ciento para sus colegas del Senado) y uno de casi 35 por ciento para gastos ordinarios de los partidos políticos a quienes ellos representan.

Lo que sí resulta sorprendente y constituye un acto de responsabilidad inusitada es que un partido político presente un punto de acuerdo para auto-reducirse el 20 por ciento de los ingresos que le corresponderían de ser aprobado el Presupuesto. Eso es lo que hizo el Partido Alternativa Socialdemócrata, el partido que recibe el menor monto de financiamiento público y el que menos recursos obtiene en la Cámara de Diputados.

El punto de acuerdo del PASC fue combatido en la tribuna del pleno y gracias a la acción concertada de PRI y PRD no pudo ser aprobado como de urgente y obvia resolución. El primero se ausentó para evitar el quórum de dos tercios que exige este tipo de procedimiento. El segundo simplemente votó en contra.

Las críticas fueron desde que la intención del PASC era dar un golpe mediático, hasta que si a los partidos les reduces el financiamiento desaparecerían (sic) pues no tendrían recursos para estar presentes en el radio y la televisión o que tendrán que buscar patrocinadores ilegales, esto es, que acabarían penetrados por recursos ilegítimos.

En algún momento de sus discursos tanto el PRI como el PRD han argumentado la necesidad de disminuir los recursos destinados a los partidos. En sus plataformas electorales aparece esta propuesta. Más aún, legisladores de ambos partidos fueron autores en 2004 de una iniciativa de ley que como tantas otras acabaron en la congeladora y en la que se planteaba una fuerte reducción en el financiamiento a los partidos y a las elecciones. Sin embargo, a la hora de votar nos dicen: siempre no.

¿Cómo interpretar esta negativa? No hay mucho margen. Pareciera que los legisladores escriben sus iniciativas para justificar su existencia -su razón de ser como diputados o senadores- o para obtener atención mediática, pero en realidad no tienen la menor intención de concretarlas.

En su rechazo al punto de acuerdo nos dicen que la medida propuesta por el PASC es insuficiente, que es una "cafiaspirina" al problema electoral, que es un "parche", que hay que estudiarla a profundidad y que hay que incorporarla a una reforma electoral integral (PRD) o a una reforma del Estado, también integral (PRI). Pero, que la reforma sea parcial o incompleta, ¿es argumento suficiente para rechazarla?

No hay duda de que las reformas integrales son indispensables y que la reducción del 20 por ciento al financiamiento de los partidos es insuficiente. A ella habría que agregar la legislación sobre propaganda electoral en los medios electrónicos, la disminución en los tiempos de campaña, la revisión de los altísimos gastos de campaña, la regulación de las pre-campañas, la compactación de los calendarios, el fortalecimiento del IFE para fiscalizar a los partidos y la revisión misma de la enorme burocracia electoral. Todas estas medidas forman parte tanto de la iniciativa presentada por el PRI-PRD como de la que presentó el Ejecutivo antes de las elecciones de este año y que muchos conflictos nos habrían ahorrado de haber sido aprobadas.

Pero tampoco hay duda de que la vía de las grandes reformas no está funcionando y que lo mejor es enemigo de lo bueno. Ante la negativa de los partidos de ponerse de acuerdo en esas grandes reformas que el país necesita y que no acaban de llegar, no queda más que intentar el simple principio de: por algo se empieza. Lo que en política pública se llama la vía incremental.

Golpe mediático o no, es necesario reconocer que con la presentación del punto de acuerdo, el PASC está exhibiendo un ejercicio de congruencia poco usual y está atendiendo una demanda generalizada que, por lo demás, tendría el efecto de devolver a los partidos algo de la legitimidad perdida.

No sobra decir que, en un contexto en el que los ingresos para el 2007 serán menores, en el que las propuestas para fortalecer las finanzas públicas simplemente no existen y en el que cada sector afectado por un recorte presupuestal moviliza a sus fuerzas para evitar ser tocado, la propuesta del PASC no puede ser más que bienvenida.

Líder católico golpea a mujer que defiende el matrimonio para todos

Catholic Leader Assaults Gay Marriage Supporter at Rally

Larry Cirignano, executive director of the Catholic Citizenship group, was speaking at an anti-gay marriage rally in Worcester, Massachusetts, and reportedly left the podium to assault a woman who was there to counter-protest:

Larry Cirignano, executive director of the Catholic Citizenship group, was speaking at an anti-gay marriage rally in Worcester, Massachusetts, and reportedly left the podium to assault a woman who was there to counter-protest:

"Sarah Loy (left), 27, of Worcester was holding a sign in defense of same-sex marriage amid a sea of green 'Let the People Vote' signs when Larry Cirignano of Canton, who heads the Catholic Citizenship group, ran into the crowd, grabbed her by both shoulders and told her, 'You need to get out. You need to get out of here right now.' Mr. Cirignano then pushed her to the ground, her head slamming against the concrete sidewalk...Ms. Loy was holding a sign that read, 'No discrimination in the Constitution' and counter-demonstrators were chanting, 'You lost, go home, get over it,' when she was pushed to the ground. Afterward, Ms. Loy, in tears, arose and yelled to no one in particular, 'That’s what hate does. That’s what hate does.'"

Pathetic. These Massachusetts wingnuts are so backed into a corner because their bigotry is not succeeding in that state that they're resorting to violence."

domingo, diciembre 17, 2006

La persona del año de 2006

Dec. 25, 2006 |

- Person of the Year

- Cover Story: Person of the Year: You Yes, you. You control the Information Age. Welcome to your world.

- Power to the People Meet 15 citizens—including a French rapper, a relentless reviewer and a real life lonely girl—of the new digital democracy

- The YouTube Gurus How a couple of regular guys built a company that changed the way we see ourselves

Now It's Your Turn

The other day I listened to a reader named Tom, age 59, make a pitch for the American Voter as TIME's Person of the Year. Tom wasn't sitting in my office but was home in Stamford, Conn., where he recorded his video and uploaded it to YouTube. In fact, Tom was answering my own video, which I'd posted on YouTube a couple of weeks earlier, asking for people to submit nominations for Person of the Year. Within a few days, it had tens of thousands of page views and dozens of video submissions and comments. The people who sent in nominations were from Australia and Paris and Duluth, and their suggestions included Sacha Baron Cohen, Donald Rumsfeld, Al Gore and many, many votes for the YouTube guys.

This response was the living example of the idea of our 2006 Person of the Year: that individuals are changing the nature of the information age, that the creators and consumers of user-generated content are transforming art and politics and commerce, that they are the engaged citizens of a new digital democracy. From user-generated images of Baghdad strife and the London Underground bombing to the macaca moment that might have altered the midterm elections to the hundreds of thousands of individual outpourings of hope and poetry and self-absorption, this new global nervous system is changing the way we perceive the world. And the consequences of it all are both hard to know and impossible to overestimate.

There are lots of people in my line of work who believe that this phenomenon is dangerous because it undermines the traditional authority of media institutions like TIME. Some have called it an "amateur hour." And it often is. But America was founded by amateurs. The framers were professional lawyers and military men and bankers, but they were amateur politicians, and that's the way they thought it should be. Thomas Paine was in effect the first blogger, and Ben Franklin was essentially loading his persona into the MySpace of the 18th century, Poor Richard's Almanack. The new media age of Web 2.0 is threatening only if you believe that an excess of democracy is the road to anarchy. I don't.

Journalists once had the exclusive province of taking people to places they'd never been. But now a mother in Baghdad with a videophone can let you see a roadside bombing, or a patron in a nightclub can show you a racist rant by a famous comedian. These blogs and videos bring events to the rest of us in ways that are often more immediate and authentic than traditional media. These new techniques, I believe, will only enhance what we do as journalists and challenge us to do it in even more innovative ways.

We chose to put a mirror on the cover because it literally reflects the idea that you, not we, are transforming the information age. The 2006 Person of the Year issue—the largest one Time has ever printed—marks the first time we've put reflective Mylar on the cover. When we found a supplier in Minnesota, we made the company sign a confidentiality agreement before placing an order for 6,965,000 pieces. That's a lot of Mylar. The elegant cover was designed by our peerless art director, Arthur Hochstein, and the incredible logistics of printing and distributing this issue were ably coordinated by our director of operations, Brooke Twyford, and director of editorial operations, Rick Prue. The Person of the Year package, as well as People Who Mattered, was masterfully overseen by deputy managing editor Steve Koepp. Designing a cover with a Mylar window does create one unanticipated challenge: How do you display it online when there's no one standing in front of it? If you go to Time.com, you'll see an animated version of the cover in which the window is stocked with a rotating display of reader-submitted photos. Maybe you'll see yourself.

Llorar ante Dios

"VATICAN CITY - Pope Benedict XVI’s personal preacher asked the pontiff on Friday to declare a day of fasting and penance to publicly declare repentance and to express solidarity with the victims of clerical sex abuse.

In a strongly worded lecture, he denounced the “abominations” committed inside the church “by its own ministers and pastors” and declared that the Roman Catholic Church had “paid a high price for this.”

“The moment has come, after the emergency, to do the most important thing of all: to cry before God,” the priest, the Rev. Raniero Cantalamessa, said in the first of a series of pre-Christmas lectures in the presence of the pope in a Vatican chapel..."

El Vaticano no quiso comentar sobre lo dicho por Cantalamessa.Sí, que los sacerdotes que abusaron y los jerarcas que encubrieron lloren puede ser un buen inicio, pero ¿eso aliviará el dolor de las víctimas? No creo...

sábado, diciembre 16, 2006

viernes, diciembre 15, 2006

Historias de dos ciudades

All that glisters...

A lot of cities harbour the desire to become a financial centre. Nowhere, however, has been as bold as Dubai.

The new New York

Michael Bloomberg sets out a bold new vision for his city.

Ambas ciudades están compitiendo además por construir los edificios más altos de la Tierra - con muchas otras, especialmente en Asia. Wired presenta el skyline que verá el mundo en 2012, y es que entre 2001 y 2012 el mundo verá más rascacielos que los construídos en el siglo XX.

jueves, diciembre 14, 2006

bajan...

Días pesados, y vienen unos peores. Siento que no me puedo comunicar, o ¿será que no me escuchan? Ya no sé, solo espero irme un poco de vacaciones y descansar, porque tendré que regresar, a lo que parece será el infierno... pero espero que sirva de algo, porque, ¿existe algo peor que el infierno? Deseenme suerte...

Globalización, 2006

Un amigo historiador me dijo hace poco que la historia humana se puede resumir en dos palabras: Occidente ganó. Entendiendo a Occidente como a una cultura que busca (a través de la democracia, la ciencia y el mercado) que todos cada vez sepan más y mejor, y busca que la información fluya cada vez más de manera libre, creo que tiene razón...

El PRD contra la ciencia

Hoy el partido Alternativa presentó un punto de acuerdo en la Cámara de Diputados para que el IFE reduciera en 20% el presupuesto de los partidos y se usara ese dinero en el desarrollo de ciencia y tecnología, aproximadamente 500 millones de pesos, o 10 veces el presupuesto anual de El Colegio de México. Adivinen cual fue el único partido que votó en contra: elPRD. Más rápido cae un hablador que un cojo...

(vía El Universal)

miércoles, diciembre 13, 2006

Astronautas en riesgo ante tormenta solar

La tormenta está a punto de llegar a la Tierra y puede dañar sistemas eléctricos, eso sí, habrán increíbles auroras boreales en las zonas cercanas a los polos.

¿Por qué no paga impuestos la iglesia católica?

Pero la iglesia católica se cree inmune no sólo al gobierno, sino a los fieles mismos. El pasado viernes Norberto Rivera fue a la iglesia de San Juan Bautistas en Coyoacán y un grupo de católicos lo abucheó y lo acusó de encubrir a pederastas. El Cardenal Rivera mandó cerrar la iglesia para que no entraran más fieles y fustigó a los sacerdotes por según él azuzar a los fieles, pero los fieles no actuaron por consigna, actuaron de forma espontanea. Ahhh, pero como molesta a la jerarquía católica la libertad. El autoristarismo (archivo en pdf) siempre ha sido lo suyo, como analiza Nicolás Pineda en este artículo publicado en Este País. De no democratizarse, afirma, la iglesia seguramente el camino que camina en Europa: el de la irrelevancia. Pero aquí hay un truco para despertarla: dejen de darle dinero. Cero limosnas esta navidad, y verán que rápido Norberto y cia empezarán a inquietarse, y es que a estos rufianes ya solo les gusta una cosa: el dinero, y sus privilegios.

Los poderes fácticos mandan

Los poderes fácticos mandan

De vez en vez alguien me dice que es pura retórica de izquierda decir que los poderes fácticos son quienes ejercen el poder en nuestro país. De vez en vez me dicen que es una exageración decir que las decisiones políticas en nuestro país se toman en restaurantes, bares, y lobbys de hotel.

Sin embargo el día de hoy hay tres primeras planas en periódicos de circulación nacional, que nos muestran que no es ninguna exageración decir que los poderes fácticos mandan.

1) Elba Esther Gordillo manda en la SEP, su yerno fue nombrado ayer Subsecretario de Educación Pública (REFORMA)

2) Las industrias tabacaleras y la industria refresquera manda sobre el congreso. (EL UNIVERSAL)

3) Las televisoras mandan sobre la SCT y los reguladores de competencia impidiendo la entrada una tercera televisora. (LA JORNADA)

Estas tres cosas se discuten poco frente al ojo público y mucho en espacios privados.

¿En serio alguien puede imaginar que las negociaciones con Elba Esther, con las televisoras, y con las tabacaleras y refresqueras sucede en espacios diferentes a los restaurantes, lobbys de hotel, y bares?"

Andrés, como es costumbre no deja títere sin cabeza, y lo que es mejor, con argumentos bien hechos...PD. Y porfavor no se pierdan su crónica reciente sobre Rousseau en Oaxaca.

¿El regreso de Jack the Ripper?

lunes, diciembre 11, 2006

Pinochet , Juan Pablo II y el referente nazi

El Papa Juan Pablo II dándole la mano al dictador chileno Augusto Pinochet en 1987. A pesar de que algunos dicen que el Papa presionó el dictador a ser más democrático, Pinochet logró que el polaco lo acompañara al balcón del palacio presidencial y apareciera ante el mundo respaldando al régimen, y no lo llevaba a a rastras...

La verdad no me extraña esta foto, porque tiene referentes de otra dictadura, pero en la Alemania Nazi, con el nuncio papal saludando a Adolfo Hitler. Plus ca change, plus c´est la même chose... Más evidencia sobre la relación entre la iglesia católica y el autoritarismo:

- Fotos que muestran la complicidad de la Iglesia Católica y el Nazismo.

- La iglesia católica indeminiza a esclavos del nazismo que trabajaron para ella en Alemania.

- La ONU acusa al Vaticano de encubrir a criminal de guerra.

- Y la promoción del anti semitismo por el catolicismo fue muy real. Ratzinger ha sido cómplice de ello. Dominus Iesus fue su última colaboración hacia ello, afirmando que el judaísmo y todas las demás religiones eran "deficientes".

- Y Ratzinger fue un soldado nazi, y a pesar de lo que él dice , sus vecinos afirman que estaba orgulloso de ello, como bien lo reportó el Times de Londres.

Norberto culpa a los medios por abusos de sacerdotes pederastas

Epidemia de coléra en Londres

"The brilliance of Snow’s map lay, as Johnson argues, in the way that it layered knowledge of different scales—from a bird’s-eye view of the structure of the Soho neighborhood to the aggregated mortality statistics printed in the Weekly Return to the location of neighborhood water supplies—all framed by particular understandings of how people tended to move about in the neighborhood, of the physical proximity of particular cesspools to particular wells, and of the likely behavior of specific, still invisible, and still unnamed pathogens. A city is a concentration of knowledge as much as it is a concentration of people, buildings, thoroughfares, pipes, and bacteria. Maps like Snow’s allowed the modern city to remake itself and to understand itself in a new way."

Si quieren entender un poco mejor las epidemias - que son también hechos sociales, políticos e históricos - no sólo del pasado y el presente, sino del futuro, no dejen de leer este libro.

La reseña del Wall Street Journal hace la pregunta clave: ¿puede una mega ciudad digerir su propia basura?

Pueden ver el corto promocional del libro en You Tube o comprarlo en Amazon.

domingo, diciembre 10, 2006

Las ideas de 2006

sábado, diciembre 09, 2006

Ganó

"Quod vides perisse perditum ducas" - Catullus.

"Quod vides perisse perditum ducas" - Catullus.Lo que ves está pérdido, pérdido descansa.

Una de mis luchas por un mundo mejor, con mayor dignidad y gozo, parece fue pérdida por mí, y ganada por él... Espero me tengan paciencia si este blog se convierte en algo diferente, o yo me convierto en algo diferente. De todas formas, gracias por venir...

¿El ser "sacerdote" es una enfermedad mental?

¿Qué diferencia hay entre una persona promedio y otra que afirma dedicarse de tiempo completo al "servicio de Dios"? La diferencia estribe en que los últimos afirman seguir un "destino", es decir, creen que "Dios" - claro, encarnado en una jerarquía humana, casi siempre de hombres ancianos y ricos - les confiere un destino especial para servirlo. Así lo creen desde numerarios del Opus Dei hasta sacerdotes y monjas por ejemplo. Pero hay más... Este cambio empieza con una historia, donde estas personas se sienten perdidas o alejadas del "mundo" y dicen que Dios los llama a seguirlo, salvándolos así del mundo mismo y todo lo que puede conllevar: como tener pareja o una familia. Comenta Walter Davis:

¿Qué diferencia hay entre una persona promedio y otra que afirma dedicarse de tiempo completo al "servicio de Dios"? La diferencia estribe en que los últimos afirman seguir un "destino", es decir, creen que "Dios" - claro, encarnado en una jerarquía humana, casi siempre de hombres ancianos y ricos - les confiere un destino especial para servirlo. Así lo creen desde numerarios del Opus Dei hasta sacerdotes y monjas por ejemplo. Pero hay más... Este cambio empieza con una historia, donde estas personas se sienten perdidas o alejadas del "mundo" y dicen que Dios los llama a seguirlo, salvándolos así del mundo mismo y todo lo que puede conllevar: como tener pareja o una familia. Comenta Walter Davis:"This story is the key to the nature of the transformation it celebrates and the absolute split that transformation produces. A subject finds itself lost in a world of sin, prey to all the evils that have taken control of one's life. A despair seizes the soul. One is powerless to deal with one's problems or heal oneself because there is nothing within the self that one can draw on to make that project possible. The inner world is a foul and pestilent congregation of sin and sinfulness. And there's no way out. One has hit rock bottom and (so the story goes when it's told best) teeters on the brink of suicide. And then in darkest night one lets Him into one's life. And all is transformed. Changed utterly. A terrible beauty is born. Before one was a sinner doing the bidding of Satan. Now one is saved and does the work of the Lord. The old self is extinguished. Utterly. One has achieved a new identity, a oneness with Christ that persists as long as one follows one condition: one must let him take over one's life. Totally. All decisions are now in Jesus' hands. He tells one what to do and one's fealty to his plan must be absolute. There can be no questioning, no doubt. For that would be the sign of only one thing-the voice of Satan and with it the danger of slipping back into those ways of being that one has, through one's conversion, put an end to forever. The person or self one once was is no more so complete is the power of conversion. A psyche has been delivered from itself. And it's all so simple finally, a matter of delivering oneself into His will, of following His plan as set forth in the Book and of letting nothing be within oneself but the voice of Jesus spreading peace and love throughout one's being.

The most striking thing about this narrative is the transparent nature of the psychological defense mechanism from which it derives and the rigidity with which it employs that mechanism. Splitting. Which as Freud and Klein show is the most primitive mechanism of defense employed by a psyche terrified of its inner world. The conversion story raises that mechanism to the status of a theological pathos. Though the story depends on recounting how sinful one's life once was(often in great even "loving" detail) the psychological meaning of conversion lies in its power to wipe all of that away. Magically one attains a totally new psyche, cleansed, pristine, and impermeable. One has, in fact, attained a totally new self-reference. The self is a function of one's total identification with Jesus. Consciousness is bathed in his presence. It has become the scene in which his love expresses itself in the beatific smile that fills ones face whenever one thinks of one's redemption, the tears that flood one's blessed cheeks, the saccharine tone that raises the voice to an eerie self-hypnotizing pitch whenever one finds another opportunity to express the joyous emotions that one must pump up at every opportunity in order to keep up the hyperconsciousness required to sustain the assurance of one's redemption. The whole process is a monument to the power of magical thinking to blow away inner reality, and as such a further sign of the primitive nature of the psychological mechanisms on which conversion depends."

Un gran texto, que Davis enfatiza en el caso de los fundamentalistas, pero también se aplica bien a todos quienes creen que sirven a Dios poniéndose en segundo lugar, olvidándose de la segunda parte del resumen de toda la ley: Amarás a tu prójimo, como a tí mismo. Y es notorio ver como en la jerarquía se olvidan de amarse a sí mismos, tratando se llenar ese vacío de amor con riqueza (sólo vean el BMW del párroco de San Jacinto en San Angel, la Ciudad de México), alcohol (la creciente cantidad de sacerdores con adicciones en impactante) o el sexo casual (dejando de lado los casos de pederastas, es llamativo saber como los novicios tienen relaciones sexuales con sus superiores, y como crece el número de sacerdotes con sida...)... Y todo por olvidar la segunda parte de toda la ley, y como la cumplen, tampoco cumplen la primera. Así, quienes se supone deben "pastorear", se convierten en lo que quisieron no ser, lobos.

Otro texto interesante es un artículo de Luis A. Várguez Pasos (archivo en pdf), de la Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Titulado "La "guerra espiritual" como discernimiento vocacional: ¿ser sacerdote o estar en el mundo?", el artículo analiza las experiencias de doce ex seminaristas del Seminario Conciliar de Yucatán, ante la decisión, de primero, entrar a esta institución y, luego, salir de ella. Fue publicado en el número de invierno 2006 de la revista Relaciones de El Colegio de Michoacán.

Tsunami en el sol

"The tsunami-like shock wave, formally called a Moreton wave, rolled across the hot surface, destroying two visible filaments of cool gas on opposite sides of the visible face of the Sun.

Astronomers using a prototype of a new solar telescope in New Mexico recorded the action.

"These large scale 'blast' waves occur infrequently, however, are very powerful," said K. S. Balasubramaniam of the National Solar Observatory (NSO) in Sunspot, NM, "They quickly propagate in a matter of minutes covering the whole Sun, sweeping away filamentary material."

It is unusual to see such an event from a ground-based observatory, Balasubramaniam said. And it was also unusual that it occurred near solar minimum, when the Sun is at its least active during an 11-year cycle."

Miren la intensidad de la tormenta que ha azotado al sol y a todo el sistema solar esta semana:

viernes, diciembre 08, 2006

Tendencias: el Reina Bruja de Madrid

Jesuitas destruyen mural de Ibarrolla

El mismo portavoz asegura que dos informes técnicos de la Diputación de Vizcaya y el Ayuntamiento de Bilbao han avalado la decisión, aunque ambas instituciones han negado este extremo.

Los responsables de Arrupe Etxea han asegurado también que antes de emprender las obras de rehabilitación se pusieron en contacto con Ibarrola, pero el artista, que ha puesto el caso en manos de sus abogados, niega que haya sido así. También niega que las pinturas estuvieran en mal estado de conservación. Para Ibarrola, "es otra más que hay que anotar en mi contra, pues no han tenido ni la delicadeza de consultarme y no quiero decir más", afirma en El Correo."

jueves, diciembre 07, 2006

Palacio de las Artes Reina Sofía, Valencia (Spain) pic # 2

Night panorama of Palacio de las Artes Reina Sofía, Valencia (Spain) pic # 2, originally uploaded by salvita_42.

Otra perspectiva, del mismo edificio que les mostré la semana pasada.

Ratzinger y Kissinger: el regalo envenenado

|

La semana pasada el National Catholic Register - retomando información del diario italiano La Stampa - informaba que el Papa Benedicto XVI - Joseph Ratzinger - había designado al Secretario de Estado como consejero personal. Hasta hoy, el Vaticano no ha desmentido la información publicada.

Ratzinger y Kissinger tienen afinidades: ambos son rozan los 80 años, ambos vivieron la 2a Guerra Mundial, ambos son alemanes y ambos creen que el futuro de Occidente se juega en el Medio Oriente. Ambos se reunieron el pasado 28 de septiembre en el Vaticano (aunque La Stampa dice que fue el 29 en Castel Gandolfo, el castillo del Papa a las afueras de Roma y donde está el observatorio papal manejado por la Compañía de Jesús) y se cree que fue en esa reunión privada donde Ratzinger le hizo la invitación.

En este contexto, es interesante notar que la palabra alemana para decir veneno es "regalo". Un regalo envenenado recuerda a la manzana del Arbol del Conocimiento del Bien y del Mal, recuerda a la caja de Pandora que contiene todos los males del mundo, recuerda al Caballo de Troya...

Hace poco Ratzinger dijo que la paz es otro nombre de Dios. Espero no se confunda con Kissinger, quien ganó el Premio Nobel de la Paz a pesar de haber sido uno de los diseñadores de la guerra de Vietnam, del golpe de Estado de Pinochet y de las dictaduras en América del Sur...

La pregunta que hacía hace una semana es entonces más oportuna ahora: ¿quién será el asesor de quién? ¿Quién se obsequia a quién... y cómo?

miércoles, diciembre 06, 2006

Ratzinger hace que se contradiga el Cardenal Hummes

"This question is not, then, currently on the order of the day for the ecclesial authorities, as was recently reiterated following the latest meeting of heads of dicastery with the Holy Father."

Es penoso ver como Ratzinger maneja la iglesia, como un gangster...

Padua o la libertad no ha muerto

No me asombra que haya sido Padua la primera ciudad en desafiar en este respecto al poder del Vaticano, el cual claro, ya protestó. ¿Porqué no me asombra el actuar de Padua? Porque tiene siglos desafiando la maldad de la iglesia católica.

Hace poco, debido a la presión de muchos sectores, la Santa Sede abrió parte de sus archivos sobre la inquisición, y los historiadores acudieron, y ha empezado a divulgarse lo que se ocultó ahí durante siglos. History Channel transmitió hace poco un documental basado en este material, Los Archivos Secretos de la Inquisición. En su tercer capítulo, narra lo sucedido durante el renacimiento italiano. Y mucho lo que pasa hoy se parece a ese momento...

Ratzinger se parece mucho a un antecesor suyo, al abispo Carafa que luego se convirtió en Pablo IV. Carafa persiguió a los "herejes" primero en la España de los reyes católicos, y luego en la Italia del siglo XVI, a los católicos que osaban leer los textos escritos por Lutero. Cuando fue designado Papa atacó todo pensamiento libre, especialmente en la culta Venecia, de la cual mando quemar a un monje que osó afirmar que la gente podía comunicarse directamente con Dios. También atacó la Universidad de Padua, reconocida por su excelencia y su tolerancia a las nuevas ideas. Un estudiante de derecho de 24 años fue apresado y quemado en aceite por afirmar que el Papa era simplemente un humano como todos...

Cinco siglos después Padua sigue demostrando que aún ama la libertad, y cinco siglos después Roma sigue mostrando cuanto la odia...

Actualización: 7 de Diciembre. Un día después de lo sucedido en Padua, el Senado italiano pasó una moción pidiéndole al gobierno del primer ministro Romano Prodi que proponga una legislación que soporte uniones civiles para parejas del mismo sexo. El Vaticano ha hecho saber que se opone a ésto. El pasado mes de mayo el Papa Benedicto XVI que usaría todo su poder para impedir que las parejas del mismo sexo sean reconocidas legalmente. Cuanto miedo al amor hay en Roma...

Judíos conservadores de EU permiten rabinos gays

Conservative Scholars Ease Gay Rabbi Ban

Filed at 7:39 p.m. ET

NEW YORK (AP) -- Conservative Jewish scholars eased their ban Wednesday on ordaining gays, upending thousands of years of precedent while stopping short of fully accepting gay clergy.

The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, which interprets religious law for the movement, adopted three starkly conflicting policies that nonetheless gave gays a wider role. Four committee members who wanted to uphold the ban outright resigned in protest after the vote.

One policy maintains the prohibition against gay clergy. Another, billed as a compromise, maintains a ban on male sodomy but permits gay ordination and allows blessing ceremonies for same-sex couples. The third policy supports the ban on gay sex in Jewish law and notes that some gays have successfully undergone therapy that changes their sexual orientation.

That leaves seminaries and synagogues to decide on their own which approach to follow.

The decision will test what Conservative Jewish leaders call their ''big tent'' -- allowing diverse practices by the movement's more than 1,000 rabbis and 750 North American synagogues.

''We believe in pluralism,'' said Rabbi Kassel Abelson, the committee chairman, in announcing the vote. ''We recognized from the very beginning of this movement that no single position can speak to all members of the community.''

But Rabbi Joel Roth, one of the four members who resigned, said the decision was ''outside the pale of acceptability' in Jewish law. Roth was author of the paper that upheld the ban.

The 25-member panel voted at the end of a two-day closed meeting in an Upper East Side synagogue. Students from Keshet, a gay advocacy group at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the flagship school of Conservative Judaism, huddled outside as they awaited the results.

Jay Michaelson, director of Nehirim, a group that provides spiritual retreats and other programing for gay Jews, said he was ''pleased not thrilled'' about the vote.

Conservative leaders are facing the issue as they struggle to hold the shrinking middle ground of American Judaism, losing members to both the liberal Reform and the traditional Orthodox branches.

Reform Jews, as well as the smaller Reconstructionist branch, allow gays to become rabbis; the Orthodox bar gays and women from ordination. The Reform movement praised the committee's vote Wednesday, while the Orthodox called it a rejection of ''authentic Torah traditions.''

It's unclear whether any congregations in the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, the synagogue arm of the movement, will break away because of the vote.

A handful of Canadian congregations, which tend to be more traditional than their U.S. counterparts, have said they would consider the idea. Leaders believe the more likely response is that individuals who object to the change will leave to worship in Orthodox synagogues.

The last major Law Committee vote on gay relationships came in 1992, when the panel voted 19-3, with one abstention, that Jewish law barred openly gay students from seminaries and prohibited rabbis from officiating at gay union ceremonies.

In this latest vote, the rabbis chose among five ''teshuvot'' or legal opinions. The two main opinions -- for and against lifting the ban -- received 13 votes each. An opinion needs only six votes to pass, allowing more than one paper to be accepted.

Rabbi Elliot Dorff, vice chairman of the panel and a co-author of the pro-gay legal opinion, argued that the biblical verse at the center of the debate -- Leviticus 18:22, which states, ''Do not lie with a male as one lies with a woman'' -- had been interpreted too broadly in the past.

He said Conservative Judaism's ability to ''integrate tradition and modernity'' allowed for the change.

Dorff is rector of The Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies in Los Angeles, which also trains Conservative rabbis. He said he expected the school to announce within the next several weeks that it will accept gay and lesbian applicants.

Arnold Eisen, chancellor-elect of the Jewish Theological Seminary, has said he personally supports ordaining gays. But he said in a statement Wednesday that the faculty would vote on whether they should revise the school's admissions policies. He has commissioned a survey of Conservative rabbis and lay people on the issue to inform the debate.

''We know that the implications of the decision before us are immense,'' Eisen said. ''We fully recognize what is at stake.''

------

On the Net:

Background on Law Committee vote:

martes, diciembre 05, 2006

The Little Boat

Todos vamos a la mar, y a la mar entramos.

Juntos, navegando por fuertes corrientes,

Todos vamos a la mar, y a la mar entramos,

Juntos, navegando por aguas sonrientes.

Todos vamos a la mar...

NYT: el abasto de granos de EU se va a Canadá, y el de México?

America’s Breadbasket Moves to Canada?

Agriculture researchers say the time is now to develop crops — including maize, wheat, rice and sorghum — that can resist global warming trends. (Photo: Cimmyt)

Agriculture researchers say the time is now to develop crops — including maize, wheat, rice and sorghum — that can resist global warming trends. (Photo: Cimmyt)At its annual general meeting in Washington yesterday, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, the world’s leading network of agricultural research centers, said the steady march of global warming was driving the need to develop new crop strains that can withstand rising temperatures, drier climates and increased soil salt content, as well as “boosting agriculture’s role in removing greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere.”

In a news release about the meeting, the group explained:

The world’s population is expected to increase by 3 billion people by 2050. In a world where 75 percent of poor people depend on agriculture, climate change will have a profound impact on their food security.

Higher temperatures in Latin America, Asia, and Africa will shorten growing seasons. Changes in rainfall patterns may lead to droughts in some areas and to floods in others. Researchers have estimated that a rise in temperature and change in rainfall could result in losses amounting to as much as $2 billion a year through reduced yields of important food crops such as maize. In other regions of the South, farmers will face greater climate variability, including more frequent and sustained intense weather events such as droughts, floods, and typhoons.

BBC News noted on Sunday, in its pre-coverage of the conference, that the rising temperatures will, of course, have an impact not just on poor countries, including opening up parts of North America and Russia to wheat production that are currently too cold — including Alaska and Siberia. Indeed, a map based on research by Cimmyt, a nonprofit network of global organizations working on food security and agricultural issues, shows the belly of North America’s wheat bounty shifting to Canada by 2050.

Via BBC News.

Via BBC News.Christopher Mims at the Scientific American blog noted yesterday that this would put America’s breadbasket squarely north of the border, and asked “if that’s what will happen to wheat, what’s going to happen to other key crops, like soybeans and corn?”

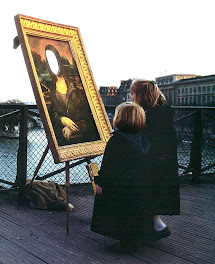

De los tesoros de Wikimedia

Buenos augurios

Federico Reyes Heroles

Federico Reyes HerolesBuenos augurios

"La madurez del espíritu comienza cuando dejamos de sentirnos encargados del mundo".

Nicolás Gómez Dávila

Fox llegó borracho de gloria. Calderón tupido de golpes. Fox inició la fiesta desde el primer minuto: sus hijos antes que la República. Calderón rindió la protesta, 62 palabras, ni una más ni una menos. Fox pisoteó la vida simbólica, desde la aparición del crucifijo hasta la torpe declaración de que él pondría la banda a Calderón. No entendió nada. Calderón tuvo que recordar al presidente de la Cámara que era él quien debía recibirla del ex Presidente. Fox anunció la refundación de la República. Calderón, que no habrá refundación y sí en cambio continuidad donde es debido. Fox llegó utilizando el pasado como arma de ataque. Calderón propuso mirar para enfrente. Fox exageró con tal de trepar en su popularidad de autopropuesto salvador de la patria. Calderón matizó con oficio. Fox ofendió desde el primer minuto. Calderón ofreció gobierno para todos y diálogo para quien lo quiera. Fox llegó entre aplausos por la puerta de enfrente, salió entre silbidos por la de atrás. Calderón llegó por la puerta trasera y sorprendió a todos. Si cumple saldrá por la de enfrente.

Nada hay que inventar, los contrastes están allí a flor de piel. Gran estatura y gran frivolidad. Mediana estatura y gran seriedad. Cinturón, botas, guasas, ofensas, palabrotas, todo como expresión de una enorme inseguridad que busca disfrazarse de algún vacuo estilo. En Calderón no hay distracción exterior: es un mortal de a pie, vestido de mortal de a pie. Pero si en el exterior brincan las diferencias, las de fondo son aún mayores. Fox ejerció un profundo desprecio por la palabra política, por el saber, por la cultura. Calderón comenzó rescatando a la palabra como instrumento de concordia y no de rencor. Calderón es estudioso y sabe qué quiere. Fox sólo sabía lo que no quería: al PRI, a López Obrador. Fox llegó embelesado con su gran atractivo personal. Calderón de entrada responsabilizó a los tres poderes y a los tres órdenes de gobierno. Fox huyó sistemáticamente de las confrontaciones ineludibles por el propio ejercicio de la autoridad, inexorables en un estadista: confrontaciones con la violencia como chantaje, con los grandes poderes monopólicos, con el corporativismo degradado. Calderón comenzó cumpliendo con la cita de violencia anunciada.

Fox despreció a las instituciones porque venían de la herencia priista, a todas, parejo. Calderón comenzó con un reconocimiento a las Fuerzas Armadas y en general a las instituciones. Si se necesitan ajustes, adelante. Pero nada de condenar parejo y por capricho. Fox con imprudencia majadera revivió un asunto que divide a los mexicanos y que estaba en paz: la religión en la vida pública. De entrada la Basílica televisada, el crucifijo y las menciones de Dios que conducirían al beso en el anillo y los tres tronos incluido el de su esposa durante la visita papal. Calderón no tuvo el menor empacho en hablar de las madres solteras e invocar a Juárez.

Fox recibió de Zedillo un país en orden y con un amplio margen de maniobra. Fox hereda un país dividido con enorme déficit de legalidad, seguridad, y con un desgobierno galopante. Oaxaca como referente obligado. Pensiones, energéticos, Pidiregas equivalentes al 6 por ciento del PIB, ahorro interno a la baja y caída en términos proporcionales de la inversión extrajera directa, muchos pendientes. Productividad en picada como foco rojo permanente. Por si fuera poco hereda enemistades con casi todo el continente: de Estados Unidos a la Patagonia. Es curioso, han sido esas instituciones que tanto denostó Fox las que sostuvieron la República a pesar de Fox. Allí estuvo el IFE para encauzar la elección más difícil del México contemporáneo, atizada por el intento de desafuero. El Tribunal Electoral para encauzar legalmente la inconformidad surgida en buena parte por la imprudente participación de la Presidencia en el proceso. Allí estuvo el Heroico Colegio Militar para recibir la Banda en la extraña ceremonia-fusible del jueves por la noche. Allí estuvo el Estado Mayor Presidencial para administrar la maniobra de toma de posesión; allí estuvieron los relevos en la Secretaría de la Defensa y Marina cuya lealtad institucional nadie pone en duda. Allí estuvo la PFP para resguardar los recintos de las ceremonias. Las instituciones dieron a Fox el trato que se merecía. A la inversa no ocurrió lo mismo.

Pero quizá la mayor diferencia radique en la actitud hacia la política. Fox menospreciaba e incluso despreciaba el trabajo político. De allí su incapacidad para tender puentes y construir acuerdos. Calderón, en cambio, está formado en esas lides: la discusión en el Legislativo, la convivencia con los adversarios. Las diferencias no le resultan afrenta, así lo dijo y es creíble. Calderón no llega con ánimo de vendetta en contra de un pasado del cual nadie o todos somos responsables. Llega a hacer política y no campaña. Sabe que sus logros dependerán de su habilidad para navegar en aguas encontradas. Sabe que debe atender a la ciudadanía, de ahí los señalamientos a la desigualdad e injusticia social. Sabe que para satisfacer esas inquietudes debe actuar, sean las decisiones producto del diálogo, de consensos o no. Por lo expresado en su mensaje está muy consciente de que la política o los políticos no deben convertirse en obstáculos para mover al país.

Hace seis años todo era fiesta y sin embargo hubimos algunos pesimistas que afirmamos que las primeras señales eran pésimas. Hoy los nubarrones dominan y sin embargo soy optimista. Las primeras señales hablan de consistencia y oficio. Ojalá y así se conserve. Al parecer la adversidad le sienta bien a Calderón. Qué bueno porque habrá mucha.