Me encanta la hibrización, lo impuro, lo que mezcla, como este aprendizaje. Copio del NYT: Learning From Tijuana: Hudson, N.Y., Considers Different Housing Model

PARC/Estudio Teddy Cruz

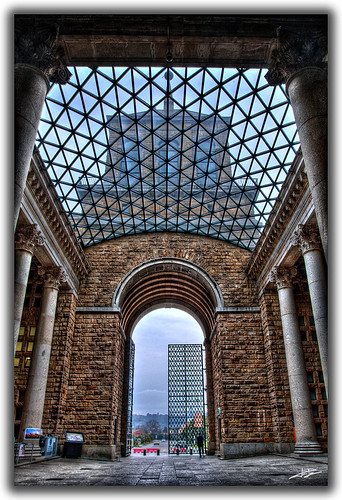

Teddy Cruz’s housing proposal for Hudson, N.Y. The development would feature playgrounds, an outdoor amphitheater and spaces that could be used for arts or job-training programs.

More Photos >

Published: February 19, 2008

If you doubt that the derelict shantytowns of Tijuana could work as a template for redevelopment in a quaint, upscale town in the Hudson River Valley, you’re probably underestimating Teddy Cruz.

Mr. Cruz, an architect and professor at the University of California, San Diego, has spent the better part of a decade strolling through Mexico’s bustling border towns in search of inspiration. Where others saw poverty and decay, he saw the seeds of a vibrant social and architectural model, one that could be harnessed to invigorate numbingly uniform suburban communities just across the border.

“Developers in Tijuana would build entire neighborhoods of generic 400-square-foot houses — miniature versions of suburban America,” Mr. Cruz said in an interview. “What I noticed is how quickly these developments were retrofitted by the tenants.” Informal businesses like mechanics’ shops and taco stands would quickly sprout up on the front lawns and between the houses, transforming them into highly layered spaces.

Mr. Cruz built a reputation by applying those lessons to the design of residential developments for Latino immigrants in suburban San Diego, enveloping simple housing units in a matrix of communal spaces.

About a year and a half ago, Mr. Cruz received an unexpected call from David Deutsch, an artist who runs a nonprofit foundation that sponsors arts programs in Hudson, N.Y. Mr. Deutsch was worried about the effects of gentrification on the town’s poorest residents, many of whom live in decaying neighborhoods just out of view of the transplanted New Yorkers and weekend antique shoppers ambling down its main strip.

Together Mr. Cruz and Mr. Deutsch set in motion an unconventional redevelopment plan aimed at reintegrating the poor and the dispossessed into Hudson’s everyday life. (The plan, which is being supported by the city’s mayor, Richard Scalera, is scheduled to go before the city council in the next few weeks.)

They began by holding a series of workshops with Bangladeshi and Hispanic immigrants and African-American and elderly residents to develop a project that grew to include communal gardens, playgrounds, an outdoor amphitheater, a co-op grocery and “incubator spaces” that could be used for arts or job-training programs.

To insert the project as gently as possible into the city’s existing fabric, Mr. Cruz broke it into six distinct developments. Then he zeroed in on a series of empty municipal lots — “leftover urban fragments,” he calls them — that serve as an informal dividing line between the decrepit working-class neighborhood along State Street and the pricey coffee and antiques shops that run parallel along Warren Street, just to the west.

His notion was to use the developments to create a series of subtle but unexpected connections between east and west, poor and privileged. In one example Mr. Cruz proposed a narrow park that would cut through a series of city blocks and connect Warren and State Streets. Along the park’s eastern edge, he would plant a mixed-use housing complex with apartments stacked like building blocks around a series of intimate public zones.

At the center of the complex he designed a raised amphitheater where tenants could sit and look out at the park below. Smaller, more private terraces overlook the amphitheater from the surrounding apartments. Each of the units has its own private entrance on the street.

Mr. Cruz also proposed to preserve a community garden several blocks to the north by surrounding it on three sides with housing and public amenities. A long covered loggia frames one side of the garden, with a greenhouse perched on top. The loggia will act as a communal porch where people can mingle, eat lunch, play chess. A row of small three-story houses frames the opposite side, punctuated by narrow alleyways that will allow people to filter into the site.

There are also more direct echoes of Mr. Cruz’s Tijuana research. In one development a day care and elderly center topped by stacked apartments would be housed in a series of garagelike spaces along a small public playground. The apartments are reminiscent of the stucco bungalows in Tijuana that are sometimes raised on steel braces to make room for new shops underneath.

Some of the apartments extend over the park like fingers, suggesting makeshift shelters. Small, shared terraces connect the affordable units to instill a sense of community. Higher up a series of market-rate apartments have private terraces, as if to assert their independence.

For iconoclasts Mr. Cruz’s design may not push enough buttons in formal architectural terms. But his great achievement here has less to do with aesthetic experimentation than with creating a bold antidote to the depressing model of ersatz small-town America embraced by so many suburban developers in recent years. In its place he proposes a complex interweaving of rich and poor, old and new, public and private, a fabric in which each strand proclaims a distinct identity.

As the flow of new immigrants into America’s suburbs makes them ripe for architectural experimentation, his insights will become only more relevant.

PD. Además el NYT editorializa hoy sobre la importancia de las ciudades y su problemática en la política electoral de 2008.